|

AN

ENCOUNTER |

|

|

|

By |

|

I staggered along the dry creek bed, sinking ankle-deep in pools of dry sand and stumbling over an occasional cobblestone, past sugar cane fields dancing in the breeze. A few cottonwoods at the edge of the valley provided me a brief respite from the burning sun, before I ventured out to the cactus country again. At every few steps, I scanned the barren foothills, above desert hackberries and creosotes, for the largest known prehispanic water retaining structure in the American continent. The panoramic photographs from Woodbury and Neely’s book[1] had etched deep in my mind a wall of well-packed rock, topped by a bell-shaped mound of earth. I was searching for the remains of the Purron Dam, a huge earth and rock pile that plugged the seasonal flow of the creek, creating a reservoir that had been nourishing the valley below for 1500 years, according to the archaeologists. As a civil engineer involved in building many dams, I now felt the anxiety of a devout Muslim on the road to Mecca. |

|

Suddenly, a long wall of rectangular blocks

of rock, jutting out of the hillside on my right, caught my eye.

I scrambled out of the creek bed and ran to higher ground to catch

a better view. The wall looked

like a perfect masonry job --cut blocks of rock placed in neat rows with

little mortar, except, it extended deep into the hill. This

time, the credit belonged to the nature.

It was a ten-foot thick layer of sedimentary rock, broken into

thin leaves as the mountain above eroded away, and exposed recently by

gravel mining. I began to

feel in my limbs the stinging pain from getting whacked and scratched

by vines and cacti during the run up. |

|

| Frustrated, I

started to doubt the wisdom of the archaeologists.

Did they know what they were looking at?

Would anyone build a dam this far above the valley, in a

stream this small? Is

there a big basin to store enough water?

Had the archaeologists been fooled by some strange

geological formation? If

I can’t even guess where the dam should be… my 20 years of

dust-breathing, sweat-bleeding civil engineering experience was on

trial too. |

|

Armed with only a sketchy map, I plunged

solo into this thorny wilderness of the Tehuacan valley of Puebla, Mexico,

trusting my sense of engineering and orienteering.

Since the archaeological investigations were some 40 years old,

I inquired in Mexico City for the present conditions at the site.

Two archaeologists who had visited the site guaranteed I could

locate it easily, though no one had attempted to restore nor mark off

the site since. No doubt

they assumed I would hire a guide from the closest town, as they had.

Yet, I wanted the gratifying exhilaration of stumbling upon the

ruins on my own. |

|

|

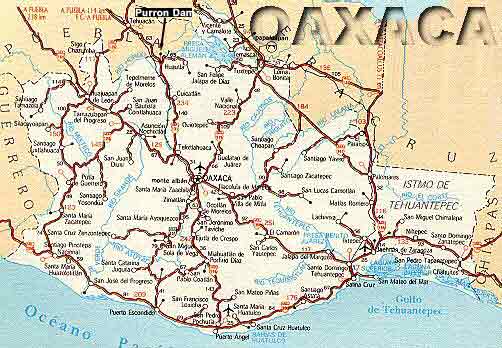

I caught the last bus from Oaxaca City to Teotitlán del Camino at the border with Puebla, spent the night there, and took an early bus towards San Rafael --the last village in Puebla. Though a complete stranger to the area, my fluent Spanish and my “mexican-look” allowed me to gather information on the street without raising eyebrows. Paying attention to passing topographical features, I located the crossing of the stream Lencho Diego in which the dam was built, and got off the bus. No houses were nearby. I followed a footpath by the stream, crossed the modern irrigation canal that feeds the sugar cane fields and walked along the dry creek bed into the arid foothills. For the next two hours, I searched for the dam along many branches of the stream, wiggling, creeping and crawling among saguaros, magueys and ocotillos but all in vain. Dejected, I turned back. Hearing a farmer at work in the cane fields, I approached him and sheepishly explained my plight. |

|

Having traveled all over the United States as a migrant worker for

decades, Don Cornelio Gonzalez immediately took pity on this lost

soul. He owns a large

part of the cane fields and also the adjoining land where I was

roaming without permission. He brushed my apologies aside “you didn’t come to steal

anything, right? I

know many crazy gringos who love to travel.” After listening to

stories of his memorable travels north of the border, I inquired

about the ancient dam. |

|

“No, I have

never heard of such a thing in this valley!” he said.

In Mexico, a prehispanic ruin would draw the attention of the authorities,

and hence the general public, only if the structure is pyramidal or if

prominent sculptures were found.

Still, he had important information to share: a large branch of

the stream flowed from a direction I hadn’t explored yet. “Thanks a lot, for being kind enough to help even an intruder” I said, and hurried towards my last hope. It was while scrambling up this branch that the visually illusive sedimentary rock formation fooled me. |

|

Now guilt nagged at me. Only

minutes ago, in front of Don Gonzalez, I glorified the Purron Dam.

Moreover, I had used it as an example in academic speeches

and technical articles, praising the designs of ancient engineers

for efficiently using the only resources they had in abundance:

manpower and time. |

|

The archaeologists estimated that the 50-foot high, 1500-foot long earthfill dam had been built in four stages, spanning over 1000 years. Once the reservoir behind the dam silted up, ending its useful life, the next stage was built on top, to increase the storage capacity of the lake. The previous stage provided a solid foundation for the new dam, which saved effort and time in earthmoving, and created a lake much larger than what one generation could build with the simple tools at hand. However, such a utilitarian design required a long-range vision and the political will to spend extra resources at the initial stages of the structure so that later stages can be added. This contrasts starkly against the modern money-driven philosophy, on which every thing is designed to last barely a marginal shift in market value. |

|

Furthermore, the

archaeological data hinted at a remarkable construction technique

that cleverly resolved both a mechanical and a labor management

problem. The

investigators had noticed a series of roughly built stone walls

within the eroded out cross section of the dam. The walls apparently formed a large grid of roughly 12-foot

square rooms covering the entire base of the dam, which were

filled and compacted with rubble and earth.

Since manual tools do not compact large volumes

efficiently, this technique helps achieve a dense dam core to

prevent water leakage. In ancient times,

such massive civil works were built using unpaid, voluntary or

tributary labor, numbered in the thousands, but comprised of

smaller cohesive units representing individual communities or

clans. Instead of

trying to regiment this motley crowd under one command, early

engineers evidently opted for a design that permitted smaller

groups of laborers to work independently, each filling one or more

internal rooms. |

|

I knew that if I gave up now --having believed

without proof the archaeological interpretation of Purron dam, doubts would

haunt my research forever. So,

I chugged along the creek bed, determined to explore all possible dam sites

upstream. A sudden stirring

of dry underbrush scared me: a rattler?

I fixed my sights on the path ahead. A

large mass of black moss, hanging from eroded roots on the left bank, was

rocking back and forth in slow motion. I recalled warnings about tropical

ants, bunched in balls waiting to attack en masse and devour the prey in

minutes. Could they be present

in the desert too? Is my endeavor

worth all this trouble? I stopped

to take stock. |

| That’s when I saw it. Exactly as I had imagined. Just before the creek wiggles out of a narrow canyon and fans down to the gently sloping valley, a huge mass of earth had plugged it. |

|

|

Eroded cross-section of the dam

|

|

The occasional floods had breached a

30-foot wide section of the dam, leaving a 50-foot tall, 200-foot long

vertical section. The cacti

had taken over the top of the dam, but the generally arid climate had

preserved the structure’s cross section intact –a full scale architectural

rendering of construction details. I could immediately identify the internal

rubble walls rising up to the level of each construction stage, unsorted

earth-and-rock roomfills, and the wide, neatly assembled retaining wall

of well-cut blocks of rock.

|

|

|

The ancient engineers had picked the best possible site for the

dam. In the first

couple of hours of exploration, my ant’s view of the topography

had fooled me into believing that the stream ended at the wall of

hills facing me, because a geological accident had prevented the

stream from coming down along the handle of the spoon-shaped

valley. Somehow, the

major branch of the stream had carved its way through a

well-concealed gap in the left flange of the valley. The dam was built right behind the gap. The abutting hills supplied sufficient material for the dam

builders to block the creek, creating a basin large enough to

capture the sporadic floods of the catchment stretching to the

hazy mountains in the horizon.

The stored water had enough gravitational force to travel

to every corner of the valley below. (Unfortunately, the archaeologists had not investigated in

detail the technology involved in the water distribution network.) |

|

|

Now I can confidently advocate reviving the ancient technology as a cure for the disastrous flops of modern civil engineering. In the mad rush to modernize, most impoverished societies transplant engineering designs prepared for utterly different situations, geographically, environmentally and socio-politically. Consequently, many projects become museums of white elephants, dragging these societies deeper into the economic bog. In contrast, indigenous engineering projects embody thousands of years of experience, their techniques having successfully weathered local conditions. |

|

In many localities, even the socio-political conditions

remain the same since the ancient times, except probably the notion

of self-reliance. Unskilled

labor, many communities’ only marketable resource remains underutilized

in favor of heavy machinery. To

offset the burdensome costs of operating such fancy tools, the engineers

tout the ability to complete a task in a hurry.

Yet, most projects sit idle or operate below capacity for years

because of lags in other infrastructure and bureaucratic corruption.

Thus, to improve the conditions at impoverished societies, the

best strategy may be to plan a project well and build it slowly at the

pace of manual labor. |

|

After Purron dam, I opted to relax at the coastal village of Tecolutla, Veracruz, where the people were just recovering from a disastrous flood that had wiped out entire blocks of houses and hotels.Further down the Atlantic coast, the city of Villahermosa and other lowland municipalities suffered worse during that rainy season. The Grijalva River, bordering the city, has 3 large reservoirs upstream, supposedly built for flood control as well as for power generation. The lowlanders, with water up to their rooftops, blamed sudden water releases from upriver dams for much of the damage. |

|

|

The heated political climate and the overly secretive government business practices prevented the truth from surfacing. Yet, many a time, the nature has caught the modern engineers napping, surrounded by outdated and malfunctioning equipment, yet falsely secure in their "nature-conquering" mindset. Time has come to rethink the way we tackle the nature. Instead of hiding under delusive and costly protection schemes, we should face the nature on an even footing and learn to live in harmony with it. May be we should ask how the Purron dam engineers, with no fancy gates available to them, would have tackled the flood. 26th June, 2000. |

|

[1] Woodbury, Richard B. and James B. Neely (1972) “Water control systems of the Tehuacan valley” in The Prehistory of the Tehuacan Valley, Ed: Richard Macneish, Vol. 4, University of Texas Press, Austin, pp. 81-153. |

Feel free to send me email if you'd like to begin a dialogue. Write to me