|

Slaves of "Free" Trade: |

|

|

|

For whom the sweat falls? |

|

By Kashyapa A. S. Yapa |

|

Two Nicaraguan women, demonstrating at Kohl’s department store in New Harrisburg, PA, had lost their jobs for demanding just 8 more pennies for sewing the $30 Kohl’s jeans in its offshore factory: if granted, their wages would have increased by a hefty 40%! (The Patriot News, Aug 19, 2000) |

|

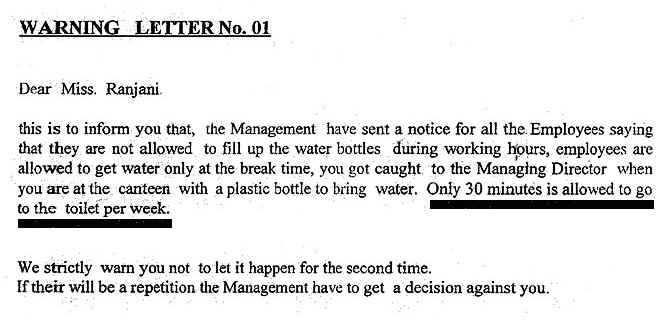

Ranjanie, a Sri Lankan worker at Sky Sports Ltd., received a warning letter, for violating company rules that allow only 30 minutes per week to use the toilets! (JAWC video, 2000) |

| One hundred and eighty eight Thai women workers perished in a fire in Kader toy factory because their building was kept locked from outside! (CAW video, 1998) |

The miserable wages and appalling working conditions in today’s assembly lines appear fairly close to those at early colonial silver smelters of South American highlands (which gave birth to assembly lines) or at Caribbean sugar mills (which set the pace for the so-called industrial revolution (Weatherford, 1988)). |

|

|

Then, the compensation kept the enslaved indigenous or African workers barely surviving. The work had no limits, no fixed hours: one worked to satisfy the demands of the mayordomo. The whip-bearer always reminded the workers how grateful they should be to have a job contributing to the well being of the empire, instead of being a burden on it. The industrial revolution seems to have come a full circle. Let us analyze its current act: the new conquerors, their weapons, the mayordomos, the slaves and also where the modern loot is headed. |

|

Bobbin, an apparel industry magazine, recently declared that (Desmarteau, 1999) the top 40 companies “have begun to streamline the supply chains,” meaning that everyone is turning towards cheap labor pools for manufacturing. Not just apparels, but every type of manufacturing that involves extensive labor use, from Disney toys to Reebok shoes, Gap fashion to Wal-Mart discount clothing, is running away from tightly-organized, high-wage, factory floors. |

|

What made this mass scale cross-border transfer of production possible? Until recently, labyrinthine rules and walls of tariffs, that supposedly protected local production, or at least the national pride, had kept the international trade a bureaucratic nightmare. After the collapse of the Soviet Union, the sole remaining powerhouse, the capitalistic nation-corporations, could pry open the closed borders with just the stick, the carrot no longer needed. On top of their perennial economic pressure tools, the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund, they added the United Nations also as a part of their arsenal, applying trade or military embargoes, if a government stops to think twice. Almost overnight, the whole world fell under the spell of the capitalistic empire. Ironically, it coerces the economically weak nations to sign “Free” Trade pacts. Yet, hordes of quotas, anti-dumping or “green” rules, enforced by “the emperor’s courts,” await whoever tries to trade the wrong way. |

|

Meanwhile, the imperial soldiers should receive not just the green light, but also the red carpet. However, unlike the conquerors of yesterday, the new empire concentrates on industrial production. |

|

This modern conquest

differs from the past in another way: the industrial flotilla does not

display the flag of the emperor. Only

a few multinational corporations bother to open factories under their

names. Instead, to do the

dirty work, they have fostered a group of intermediaries from the

second-tier capitalist nations, the so-called “Asian Tigers.”

These modern mayordomos,

together with corrupt political regimes, have created an impenetrable

mafia. In many poor countries, the traditional industrial plants, run by locals or foreigners settled down for the long haul, produced goods to substitute expensive imports. After decades of struggle, the organized work force there learned to flex its muscles and reap reasonable monetary and workplace benefits, since the employers also have a vested interest in keeping their employees satisfied. |

|

The new arrivals, the multinational companies and their subcontractors, however, have very short-term economic interests linked to a particular location, usually only till they would exhaust the local tax shelters or export quotas. Their political interests closely entwine those of corrupt local politicians, whose vision rarely extends beyond the next election and mission stops at pleasing the lenders by earning as much foreign exchange as quickly as possible. |

|

|

Thus sprang up modern slave camps, protected under special legislation that circumvents whatever labor laws that exist in the host country and policed by special militia that curtails whatever labor discontent from spreading. They aim to attract the most docile labor: the unskilled, rural, unmarried women and wherever possible, the minors. These workers, shunned by traditional employers and kept occupied previously by cottage industries, flock to the new labor camps enticed by the pay packet, barely at the official minimum level, yet much more than they would ever earn working at homes. |

|

Once at the work floor, the glimmer fades: they work 12-14 hour-days, 7 days a week, doing boring, repetitive work, without so much as a decent break to use the toilet, because the whip-bearers strictly control every second the workers takes the eyes off the production line. The supervisors have devised a mechanism of ever-increasing targets to obtain the maximum production while paying the minimum, and those who fall behind should work longer hours simply to meet the day’s target. The long work hours, the militia vigilance and corrupt politicians prevent them from taking any organized action to improve the working conditions or the salaries. |

| Can they escape the camps? No, they are trapped. The same “Free” trade that brought slave camps also destroyed whatever cottage industry existed. Ashamed to go home empty handed, they weather the physical and mental torture, until they could collect the Provident Fund money at the end of 5 years. But many get kicked out early by the heartless employers, or drop out physically handicapped, without either proper compensation or much-dreamed savings. |

|

|

The multinational companies do not necessarily locate all the “streamlined production sources” offshore, but also in the dark alleys of every big industrial city. In cold basements or in sealed warehouses of Los Angeles, New York, Paris or Munich, many undocumented workers, some trafficked by smugglers solely for this purpose, work long hours, without knowing whether it is day or night (Business Week, Nov 27, 2000). The local and national governments, bought and paid for by the same corporations, either glance away or tout the benefits of tax sheltered “enterprise zones.” |

|

No matter where

they locate these sweatshops, the costs of labor are minimal.

Traditionally, the sewn products contained a substantial

direct labor cost, around 40% of the total manufacturing cost,

which now many have reduced to 12 to 15% (Barbee, 1998).

The Tong Yang Indonesia, that produces $65 Reebok shoes,

pays about $1.00 for labor, while selling them to Reebok for

$13, after adding a margin of only about 10% (BW, Nov 6, 2000).

The National Labor Committee of New York claims that a

pair of jeans, sewn by Nicaraguan women earning only $0.20 per

piece and sold by Kohl’s for $30, has a cost of $7.14 as

recorded in US customs documents (The Patriot News, Aug 19,

2000). |

|

|

Then, where does the loot go? |

| So, who absorbs the huge gap between the manufacturing cost and the retail price? Let’s look again at the trends set by The Apparel Top 40: Bobbin says they have been “strengthening the market share” (DesMarteau 1999). Having realized that, in a saturated apparel market, prices increases bring more harm than good, the brand name power houses had begun gobbling up smaller companies and spending millions on marketing campaigns. Even a discount-end product like Wranger’s Hero jeans has planned a $30 million blitz over a year simply to capture a few percentage points in the market share (DNR, Jul 28, 2000). Men’s Wearhouse is investing $70 million in its advertising campaign aimed at setting new standards of dressing (DNR, Jun 9, 2000). Add to those the multi-million-dollar deals the apparel and sports-wear brand names sign with celebrity figures. . |  |

|

At least some socially conscious celebrities spend a part of their bonanza on charity in poor communities, but hardly do they realize that it is the poor who created that wealth, many times over, out of their sweat and blood. What could you do? ************************** Reference: Barbee, Gene (1998) “Product costing to win profit margin,” Bobbin, vol39, n12, pp. 26-28, July. Business Week (Nov 27, 2000) “Workers in bondage” Business Week (Nov 6, 2000) “A world of sweatshops” Business Week (May 3, 1999) “Sweatshop reform: How to solve the standoff” Committee for Asian Women (1998) “Dolls and Dust, ” video, 60 min. (English), Bangkok, Thailand. Daily News Record (July 28, 2000) “Wrangler’s ‘Hero’-ic effort to attract new consumers”, vol30, n88, pg.7. Daily News Record (June 9, 2000) “Men’s Warehouse’s new campaign: Business casual”, vol30, n68, pg.c1. DesMarteau, Kathleen (1999) “The Bobbin Top 40: Shape industry for next century,” Bobbin, vol40, n10, pp. 46-50, June. Joint Association of Workers Councils of Free Trade Zones of Sri Lanka (2000) “Slaves of Free Trade: Camp Sri Lanka”, video, 26 min. (in Sinhala with English subtitles), Seeduwa, Sri Lanka. Laurdee, Mehrene & Koechlin, Tim (1999) “Wages, productivity and foreign direct investment flows,” Journal of Economic Issues, vol233 n2, pp 419-426, June. The Patriot News (Aug 19, 2000) “Nicaraguan Labor leaders demonstrate outside New Harrisburg, PA retailer” Weatherford, Jack (1988) “Indian givers” Fawcett Columbine, NY.

|

| If you would like to begin a discussion, please send me an email. Write to me |