|

DISCOVERING

By

|

|

|

Heading towards Batticaloa, the capital of eastern Sri Lanka, Kamal and I

were approaching a huge cobweb of barbed wire. Dozens of barrels of tar, already caught in the web, littered

the road forcing the traffic to slow down.

Rolling forward, I noticed the sandbag-walled hide out, with mortal

AK-47 stingers lurking behind. We

braced ourselves for some rigorous searches and harsh questioning. |

|

Supposedly controlled by the government forces, Batticaloa is trapped

deep in the ever-expanding web of Sri Lanka’s ethno-political frenzy.

The ruthlessly violent conflict between the country’s two largest

ethnic groups, Sinhalese and Tamil, finds root in occasional skirmishes

from the mid-century over issues of discrimination against the minority

Tamils. The conflict

intensified in mid 1980’s as the tightening economic noose lured

opportunistic politicians to employ “divide and conquer” tactics for

short-term gains. Their

actions boomeranged, literally pulverizing many of them. The

naïve public, riled up by clannish myths and lies and used as cannon

fodder by the same politicians, also maimed and perished by hundreds of

thousands. A pain-stricken

overseas spectator of this theatrical carnage during the last decade and a

half, I was determined to use my month-long vacation to feel the pulse of

the surviving cast. My

cousin, Kamal, a government officer living in the relative safety of the

border town Ampara, had volunteered to accompany me through the

hit-and-run war zone of Batticaloa, predisposed to brave the risks. |

|

|

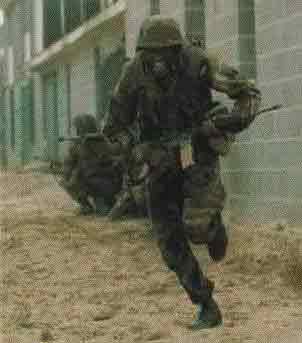

The army, dressed in olive greens with guns slung over their shoulders,

advanced, grinning and offering trays of cookies and soft drinks!

Instead of growling “where are you going?” they cajoled us,

“take more, sir, take more.” I

pulled out my camera, still hesitant, but they posed happily for me

--guns, trays and all. Finally

it dawned on Kamal. “Oh,

it’s Vesak Poya” --the most important religious day of Buddhists.

This cookies-and-drinks spectacle, unfolding repeatedly at military

barricades along the way, perplexed us. |

|

|

During Vesak Poya, many social organizations and well-off individuals set up colorful decorations and propped-up murals (Pandals) depicting religious stories, drawing thousands of people to the streets. Following the Buddhist tradition of free giving to accumulate good karma, many businesses and youth groups give away free food and beverages to the passers-by. The war-weary military of Batticaloa, mainly Sinhalese Buddhists, probably wanted to surprise the Hindu Tamils, the dominant ethnic group in the area, with this altruist tradition. |

|

|

On

any other day, the military would have confiscated my camera and jailed me

for attempting to photograph security installations.

A simple baggage search at check-points can turn into a major

hassle if the military officer cannot easily read identification papers,

or if he is merely having a bad day.

On the way to Ampara, I became exasperated at their efforts to make

me pull out every piece of clothing from my bags at the barricades, set up

mostly every 10 miles. My

slide projector contributed to the problem too, as I had wrapped it in a

blanket to cushion it from the jolts when the bus rocketed over huge holes

in the road. Noticing the

curious-looking gadget, the military wanted to check whatever else lay

hiding in my luggage. |

|

|

|

|

Such whole-hearted generosity began to suffer as the ethnic conflict

escalated. Around then, some

peasant villagers in the central hills forced me and my colleagues to

march to the community center. Only

after establishing the identity of a mutual acquaintance would they boil

the rice and dust-off the makeshift beds.

In 1990, soon after the bloodiest youth uprising in southern Sri

Lanka, I made a short-hop home after 5-years abroad and tried in vain to

learn why the South had exploded. These

Southerners, who in the past would lay out their philosophy of life on a

bus, in a coffee shop or even under a coconut tree, had their mouths under

lock and key: shell-shocked. |

|

Later, while visiting a friend in the US, I cringed listening to his

mother, who had just arrived from Sri Lanka, describing dry-eyed the

beating death of a close relative, supposedly linked to the southern

uprising. The “death

squad” had pulled him away from his wailing wife and son, exploded his

head with a stick and then dragged the unconscious man away to further

mutilate his body. Hearing the story exactly as it happened, a cold shock ran

down my spine, but telling it so seemed to help cleanse her mind. During the recent trip home in 1999, I noticed that the culture of violence had exploded island-wide. The proliferation of arms and the presence of thousands of military and paramilitary fugitives, combined with high unemployment, harsh economic pressures, and the roiling vengeance had created a market ripe for cheap, trigger-happy mercenaries. Those without the will to take revenge on others turn it back upon themselves. Sri Lanka has recently registered the highest suicide rate in the world --a symptom of the rapid devaluation of human life. Yet,

my childhood in a small southern town of Sri Lanka brings to my mind very

different images. I remember

white-clad school children lining up the roads, waiting for buses or

walking towards schools; City streets congested with pedestrians,

bicycles, bullock-carts and a few vehicles; Women balancing parasols and

grocery bags, struggling to wipe off the pouring sweat with their tiny

handkerchiefs; Men juggling the traffic, doubled under the weight of bulky

sacks on their heads or shoulders. |

|

|

|

Such

a tranquil history probably accounts for the current lack of security

consciousness in Sri Lankan society.

Upon my arrival at the international airport, I had “orders” to

pick up a refrigerator and a microwave for some relatives from the

duty-free shop. Luckily, my

brother came in a van to pick me up.

Tired and sleepy, I dreaded traveling in the wee hours of the

morning, suspecting further delays by military inspections of my

over-sized luggage. “Don’t

worry, they won’t bother us at this hour” my brother knew the

subterfuges of Sri Lankan military better. We

drove non-stop through the heart of the capital, Colombo, to my hometown

100 miles away. The logic is

that a person planning to blow up something would do so only among heavy

traffic. Therefore, the military does not bother checking late at night! |

|

Now, no place in Sri Lanka is safe, despite the overwhelming presence of the military. The Tamil guerilla group, fighting the civil war in the North and the East, can strike at will upon the military and the civilians, rich or poor, men or women, young or aged. The mercenaries neither give a hoot: they would eliminate whoever in the list of political or personal enemies of their clients with scant regard to others around. The wave of explosions that welcomed the year 2000 was planned deliberately to cause maximum havoc, targeting mainly the public buses and crowded gatherings. Equally bloody were the end-of-Presidential-election revenge attacks against media personnel and at times against entire villages --alleged political opponents of the winner. Nobody has the monopoly on cruelty. |

|

|

|

Encouraged

by the lax security in Batticaloa, Kamal picked up two local Tamil friends

to guide us. Signs of normal

life were still rare. Seeing

a school of fishermen in canoes, netting shrimp under the heavily

fortified bridge of the “Singing Fish,” I jumped out with my camera

ready. I had miscalculated. “Stop

right there!” a long black tube took aim at me.

Even before my startled cousin could step out of the car, our Tamil

friends ran towards the soldier to plead my case.

Surprised, and probably confused by the act of the Tamils, the

Sinhalese officer let me fool around. |

|

A few minutes later, on the other side of the lagoon, I tried to shoot

the “shrimpers” again, this time by edging closer to the thatched huts

by the beach. “Pleeease,

no!” the faces of our Tamil friends drained white.

“The military does not hang around here.

So?” I insisted.

“That’s exactly why.” They

would not let me move an inch towards the village.

The complexity of life in the war zone muffled me.

Were they afraid of me falling into the hands of the guerillas?

Or rather feared being seen guiding two Sinhalese around?

Back again in the government controlled area, our guides took us to the

edge of a high security zone, where no civilians are allowed.

“But why? Here I see nothing but these artificial-looking lagoons.”

I always look for reasons. “They

really are worth millions, in terms of artificial shrimp.

High level naval officers own these ponds.

Once they declare the zone ‘high security’ they can run the

business as they please, at tax-payers’ expense!” |

|

We dropped our guides and reached Ampara an hour later, when the security

forces clamped down suddenly, jeeps flying around sirens blaring,

reactivating the barricades. We

called our friends in Batticaloa. “Remember

the street corner where we showed you a burned telecom box? Right there, a suicide bomber blew up a high ranking

government supporter a little while ago!” 25th April, 2000. Feel free to send me email if you'd like to begin a dialogue. Write to me |